Preface: Taxes are not good things, but if you want services, somebody’s got to pay them so they’re a necessary evil. –Michael Bloomberg.

Historical Individual Income Tax Trends

Credit: Benuel B. Glick, EA

Overview

It has been said that death and taxes are two unavoidable facts of life. While it may not be quite that simple, there may be some truth to it. And, as the humorist Will Rogers said a century ago, “The difference between death and taxes is death doesn’t get worse every time Congress meets.” In fact, death is a much-anticipated liberation for the follower of Jesus.

In this article, we’ll briefly explore the history of America’s individual federal income tax rates. We will not look at all the shades or governmental motives for taxation. Nor will we get into excise, tariff, sales and use, corporate, investment, real estate, payroll, social security, estate and inheritance, gift, capital gains, tangible personal property, or state and local taxes. “Taxes” and “tax rates” will be referring to “individual income taxes” and “individual income tax rates” respectively.

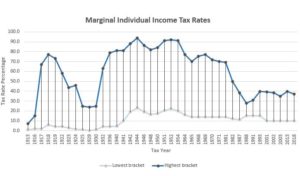

Trying to cover all the nuances of calculating the tax rates would quickly turn this article into a book, and the graph shown above only highlights overall trends since 1913. It does not reflect exemptions, phase-outs, credits, blended rates, etc. However, excluding many additional factors, it does reflect the highest and lowest marginal individual tax brackets for given time periods.

Background

With some exceptions, the American government collected the majority of its revenues from duties, tariffs and excise taxes prior to 1913. In 1913 the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified by the states – albeit with much resistance – and a new era of taxation was born. In strong opposition of the 16th amendment, speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates Richard E. Byrd warned: “A hand from Washington will be stretched out and placed upon every man’s business; the eye of the Federal inspector will be in every man’s counting house.…” Sound prophetically accurate?

Included in the 16th Amendment is the following: “The Congress shall have the power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” In short, the United States Congress was finally allowed to directly assess income taxes on individuals without permission from the states, or anyone else for that matter. It’s not difficult to guess what Congress did next.

Modest Beginnings

Initially, the tax rates appeared modest enough with taxable income under $20,000 taxed at 1%, and the highest bracket of over $500,000 taxed at 7%. That didn’t last long. In October of 1917, shortly after declaring war on Germany (WWI), Congress passed the War Revenue Act which drastically increased the tax rates. In 1918 the top bracket for income over $1M was taxed at a whopping 77%! As the saying goes, strike while the iron is hot.

The 1920’s are often referred to as the ‘roaring 20s’. World War 1 ended in 1918, and Congress nimbly lowered the top tax rates in subsequent years. The 1920’s saw a significant top rate reduction; however, it was accompanied by much lower thresholds. By 1925 the top rate was at 25%, but that included all taxable income over $100,000.

New Era of Taxation

Black Tuesday crashed onto the financial stage on October 29, 1929, and decades of high taxation followed suit. By 1940, the top tax rate was at 81.1% on income over $5M. Not satisfied with the current state of affairs, president Roosevelt actually pushed for a top tax rate of 100% and is quoted as saying to Congress in April 1942, “…I therefore believe that in time of this grave national danger, when all excess income should go to win the war, no American citizen ought to have a net income, after he has paid his taxes, of more than $25,000 a year.” In addition to his New Deal, he was calling for more funds to alleviate the WWII financial burdens. You might say he reached 94% of his goal by 1944 when tax rates had reached 94% on taxable income over $200,000!

Taxes remained high During the rest of the ‘40s and all through the ‘50s with a marginal top rate of 91% on income over $400,000 from 1954 through 1963. It’s important to maintain perspective though, an estimated fewer than 10,000 households would have reached the top bracket in 1950 per a Wall Street Journal article.

In 1964, president Lyndon B. Johnson signed the largest pre-Reagan-era tax cuts into law. A top marginal rate of 77% on income over $400,000 might sound ridiculous to the current generation, but it was a welcome relief for wealthy earners in 1964. The top rate dropped to 70% in 1965, accompanied by a threshold drop from $400,000 to $200,000. The top marginal rates bounced around within the 70-77% range during the remainder of the ‘60s and for all of the ‘70s, and were generally triggered by the top tier income over $200,000.

Modern Era of Taxation

When America’s 40th president, Ronald Reagan, was inaugurated on January 20, 1981, the economic climate was ripe for a legislative revolution of sorts. During Reagan’s tenure in office – from 1981 to 1989 – he incrementally slashed the top marginal tax rate for individuals from 70% down to 28%. It is important to note that this top rate of 28% was triggered by taxable income of approximately $30,000.

In 1993, newly elected president Bill Clinton proposed an ambitious budget to cut the national deficit in half by 1997, and signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act into law. Among many other things, this bill increased the top marginal rate to 39.6%, accompanied by a $250,000 threshold.

From 1991 through 2018 we see a consistent top rate in the 35 – 40 percent range. The top marginal rate remained at 35% with a threshold of $311,950 from 2003 to 2012. In 2013 it increased to 39.6% accompanied with a $450,000 threshold. In 2018 the top marginal rate decreased to 37% with a $600,000 threshold.

In this article we glimpsed into the historical tax trends for American individuals over a 105 year span. I’ll refrain from making a prediction for the next 105, but I am reminded of a wise saying from millennia ago: “The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9 KJV).